By Jason Snell

February 8, 2024 8:45 AM PT

Apple Vision Pro review: Eyes on the future

It’s been a very long time since Apple released a product as speculative and impractical as the Vision Pro, its $3499 first-generation “spatial computing” headset. Led by Apple, today’s technology industry sells billions and billions of dollars worth of technology to a grateful public that uses our smartphones, laptops, and other devices in nearly every aspect of our lives.

It wasn’t always this way. When I was a kid, personal computers were just beginning to arrive in homes and schools. As I anticipated the arrival of the Vision Pro, I kept remembering the earliest days of the PC, the days when Apple IIs, TRS-80s, and Commodore PETs ruled.

In those days, computer technology wasn’t practical. You’d spend the equivalent of $5000 in today’s money on a computer, bring it home, and be immediately confronted with the big question: “Well, now what?”

And yet people bought them, mostly because they got the sense that this was the first step into a new era. Being a Gen X’er means that you were probably told at some point in your young life that “computers are the future”—a meaningless statement that nonetheless turned out to be absolutely true. People didn’t know just what it all meant, but it was new and clearly where the world was headed, and for some adventurous souls (or those who broke down and listened to the begging from their kids), that was all that was required.

I first learned what buyer’s remorse felt like about 12 hours after coming home with a new computer. New computers were exciting, but then what? There was very little software available, and the suggestions your computer salesperson would give to adults were impractical things like keeping a recipe database or balancing your checkbook. As for me, I’ll just say there was a lot of 10 PRINT “JASON IS GREAT” 20 GOTO 10 in those days.

This moment very much reminds me of that moment. Like those early computers, the Vision Pro is an expensive piece of cutting-edge technology that strongly suggests a possible future. (Is it really the future? That, we don’t know.) There are very few use cases for which I can say that, yes, the Vision Pro is a smart investment at $3499. Getting a taste of the future isn’t cheap, and it’s not especially practical, but it’s such a rare opportunity that it can sometimes be worth it anyway.

Beneath the band

If there’s one thing I’m absolutely certain about when it comes to the Vision Pro, it’s this: This is the most impressive piece of Apple hardware I’ve ever seen. There will be some powerful debates about what the Vision Pro represents and what it costs, and whether or not it needs to exist… but it’s worth stopping for a moment to appreciate the technological object that Apple has designed, built, and put into mass production.

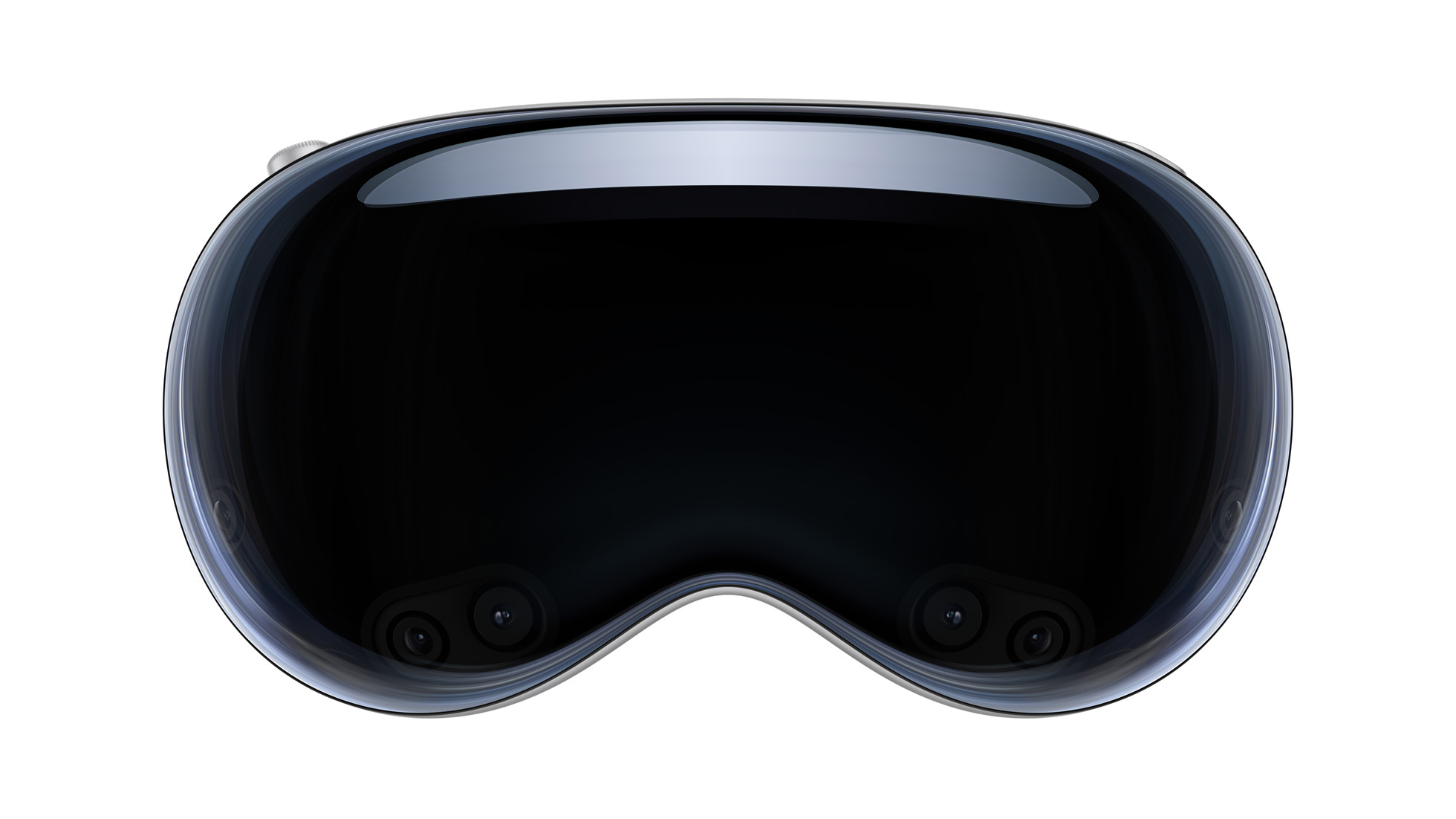

The Vision Pro is all glass and aluminum on the outside. In contrast to something like the Meta Quest 3, with its alien and off-putting triple sensor array, the Vision Pro’s black ski-goggle thing actually looks… okay?

Apple’s focus on softer materials also shines through, with lots of thoughtful fabric loops to do things like pull off one of the two included headbands or remove the included (and pleasantly soft) front cover. I’m sure Apple would have preferred to include only a single band in the box, so the presence of two—the delightful elastic, “3-d knitted” Solo Knit Band and the more utilitarian Dual Loop Band—suggests that it couldn’t find a single design that would serve everyone reliably. (I’ve also heard through the grapevine that the Solo Knit Band is more intended for short sessions, and the Dual Loop Band is better for extended use.)

I initially found the Solo Knit Band uncomfortable, putting pressure on my forehead that was immediately painful. But I found great success using the Dual Loop Band, which is far less elegant (the straps tighten via hook-and-loop attachment, while the Solo Knit Band has a dial you can turn) but felt far more comfortable initially. (Over time, as I adapted to the feel of the Vision Pro, I was also able to wear the Solo Knit Band successfully, though it was still not as comfortable as the Dual Loop Band.)

Once I got the Dual Loop Band adjusted properly, I got the answer to the question that I’ve been wondering about since I first tried the device last June: Can I use it for any real length of time without getting a splitting headache? As it turns out, yes. With the Dual Loop holding the Vision Pro firmly in place and spreading the weight across my entire head, I have been able to use it for around six hours a day without discomfort.

But that’s me. As Apple obviously found out when it was designing this thing, everyone’s head shape is unique and what works for one person won’t work for another. (I also can’t tell you if using the Vision Pro will make you motion sick, but I can tell you that it never did for me.) All I can tell you is that extended use of the Vision Pro can be done.

The rest of the Vision Pro’s standard accompaniment of accessories are the Light Seal (which attaches to the Vision Pro itself all around the interior frame), a cushion (which attaches to the Light Seal and provides comfort for the load-bearing area on your cheekbones and forehead), and corrective lenses (which are optional, but required in my case). These pieces come in different variations to fit an array of head shapes. They’re made of high-quality materials and attach magnetically. It all feels very civilized, though if you try to grab a Vision Pro by the cushion or seal, they’ll just pop off. (Fortunately, they pop right back on—the ease of magnetic attachment goes both ways.) I am slowly training myself to pick the Vision Pro up by the front hardware or the loop band, not by the light seal or cushion.

The Zeiss corrective lenses are interesting. They snap in magnetically, and I believe they’re automatically detected by the Vision Pro, but you still have to scan a card provided with the lenses in order to pair them with the device. Apparently, the Vision Pro adapts its optics based on the details of the prescription lenses that are installed. It feels like a weird extra step that shouldn’t be necessary. (If you lose the card, you can retrieve your settings from Zeiss’s website by entering the lenses’ serial number, which is inscribed on them.)

To generate Spatial Audio, the Vision Pro comes with a pair of audio pods—small directional speakers—pointed at your ears from a couple of inches away, located just where the Audio Strap (which is directly connected to the Vision Pro) connects to the head strap. The sound is aimed right at your ears, which remain uncovered.

This fits perfectly with Apple’s entire philosophy of this product, which is to overlay software (including audio playback) onto the real world rather than cutting you off from reality. When I use the Vision Pro, the sound generated by the system mixes with the sound of my real-world environment. Apple even goes so far as to process the sound to make it sound like it’s coming from your environment, using reverb and spatial effects to make things feel more natural. (The best way to notice the difference is to dial in a virtual environment while listening to audio, such as the voices from a FaceTime call. As you go from the real world to a virtual environment, the system audio will subtly change.)

The sound quality is remarkable, given that these audio pods are a couple of inches away and beaming right into my ears. They’re not as good as my AirPods Pro, and of course, everyone around me can hear what I’m listening to, too. (That’s why the first rule of Vision Pro etiquette is to use a pair of Bluetooth headphones when you’re around other people. AirPods Pro with Transparency turned on seems like the most appropriate approach if you’re going to be in a mixed environment.)

The Vision Pro has two buttons: a flat button just above the left eyebrow and a Digital Crown above the right. The left button acts as a shortcut to Capture (the Vision Pro equivalent of the Camera app) if you want to grab a spatial video or photo. It also can be double-tapped to approve a purchase in the App Store, and if you press both buttons down together, it’ll take a screenshot of your current view and place it in the Photos library.

When I first saw that Apple had put a Digital Crown on the Vision Pro, I was skeptical: As clever as it was on the Apple Watch as a riff on watch crowns, should the Digital Crown really travel elsewhere? (I don’t use AirPods Max, so I can’t judge how it’s used there.) But now I think that the Digital Crown has infected Apple’s hardware designers in a good way: They’ve discovered that there can be some delightful computer interfaces attached to a physical dial1, and since the Digital Crown is also a pressable button, it’s a much more versatile bit of hardware input.

Still, Apple’s announcement that the Digital Crown was going to be dedicated to dialing you into or out of virtual environments seemed like a bit of a stretch, reminiscent of early Apple Watch features like Digital Touch—in other words, a hardware decision based more on philosophy and tone setting than how regular people might use the product.

Now that I’ve used the Vision Pro for a while, though, I’ve come around to Apple’s point of view. The Vision Pro’s entire philosophy is about not cutting you off from reality by default, but sometimes, you want to enter a fully immersive environment to reduce distractions. Turning the Digital Crown is a pleasant, easy way to do that, and I especially appreciate the ability to dial in a certain degree of isolation—for example, just in front of me but not to the sides or back, so I can still see some of the real world.

I admit I’m still trying to figure out exactly the right times to be immersed and the right times not to be. Sometimes, it’s about anticipation: I know my wife’s in the house and is going to come and check on me in a little bit, and I don’t want to miss her when she arrives. When I’m alone, I suspect the decision will lean towards entering a more distraction-free zone. Sometimes, I write with headphones in, even if I’m home alone, because it completely isolates me from the world, and that flips a switch somewhere in my brain. I feel like turning on an immersive scene has a similar effect, so that I can exit the usual scene and enter a different—and let’s be honest, less cluttered—space. Or maybe it’s just the act of going elsewhere—like writing at a cafe instead of at my kitchen table—that puts me in a different frame of mind.

Pressing the Digital Crown is the most important single gesture on the entire device since it brings up the Vision Pro equivalent of the Home Screen: a tabbed list of apps, people, and virtual environments. Pressing and holding the Digital Crown also re-centers the entire virtual environment, which is helpful if you’ve really lost track of where all your stuff is and everything seems off-kilter.

No discussion of the Vision Pro can be complete without mentioning the device’s battery. In a battle between the elegant and the practical, practical has won out: Apple has lightened the weight of the Vision Pro hardware by tethering it to an external battery you need to keep in a pocket or next to you as you work. There’s no getting around its awkwardness, and on numerous occasions, I have gotten up only to discover I’m trailing a battery behind me.

But the truth is, most of the time I’ve used the Vision Pro, I’ve been seated. So the battery has ended up being more like a buffer to allow me to keep using the Vision Pro until I remember to plug it into power. Obviously, if you’re someplace without USB power, the two- to three-hour battery life will limit what you can do, but these days, even most airlines offer USB power to the seat.

I think Apple made the right trade-off here, but the external battery seems like the feature of the Vision Pro that will make us look back from the future and shake our heads.

Just add a keyboard, if you want to

Now let’s talk accessories. For my money, the single best Vision Pro accessory is the $99 Apple Magic Keyboard. Text input on the Vision Pro is… doable, but painful. You can either poke at a virtual floating keyboard or type by tapping your fingers together while your eyes dance from letter to letter, slowly pecking out your message.

I paired a late-model Magic Keyboard with the Vision Pro, and things got a lot better. The obnoxious floating keyboard mostly vanished, replaced by a tiny HUD that shows you what you’ve typed and gives you access to predictive text while floating right above the keyboard in a pretty remarkable bit of AR magic. The setup isn’t perfect—those floating keyboard things keep popping up and getting in the way before disappearing when I press a key—but I imagine these bugs will be shaken out in time.

You can also pair a Magic Trackpad (but not a mouse), though you’ll basically need to sit at a table or desk since it isn’t really designed for lap use.2 I sat down at my otherwise empty dining room table with a keyboard and trackpad and the Vision Pro and was able to get a lot of work done. The trackpad works inside individual apps very much like it does in iPadOS, and the pointer moves between windows with ease.

Adding a trackpad isn’t as much of a game-changer as adding a keyboard since it’s pretty easy to navigate using gaze and hand gestures. Of course, the trackpad is better at precision work, such as text selection. And using a keyboard and trackpad together certainly makes the Vision Pro computing experience seem more familiar. (Of course, if you are planning on using the Vision Pro primarily with a Mac, you can use its keyboard and trackpad to accomplish the same thing via Universal Control.)

A brand-new operating system

The Vision Pro isn’t just new hardware—it’s the start of a new Apple operating system, visionOS. Of course, visionOS is based on the same core as the operating systems that run the iPhone, iPad, Apple TV, Apple Watch, and more.

The operating system it’s most like is iPadOS; in fact, in the simplest terms the Vision Pro feels like a spatial iPad—it’s largely running iPad-style apps, except you can open a seemingly infinite number of windows and put them all around you. (That also means that we are probably due for a new battle in the iPad Wars, where some people valiantly try to get all their work done on a new Apple platform while other people angrily tell them to just use a Mac. Oh boy, can’t wait.)

Within half an hour of starting to explore visionOS, I felt something I hadn’t experienced in some time, namely the feel of using a 1.0 operating system. Newly-shipped OSes just have a certain special something about them. They’re delightfully new and yet clearly unfinished around the edges. Most commonly, I ran into issues where there was a new feature implemented in a single way, with no customization options or preferences to be set. I would also sometimes just run into weird bugs that could only be solved with a reboot. It happens. Version 1.0 is about shipping features—adding fancy customization comes later, along with a lot of bug fixes.

But because visionOS is built on such a venerable foundation—Apple’s been shipping devices running a version of this operating system for 17 years—it’s mostly functional and familiar. The Settings app on the Vision Pro will be familiar to any iPhone or iPad user. I knew just where to go to change my autocorrect settings so that the system wouldn’t automatically change what I type on a hardware keyboard—because it’s literally the same place it is on iPadOS. Once I installed the 1Password iPad app, I was able to auto-fill passwords everywhere, just as I can on my iPad. And once you learn how to access Control Center (looking up at and tapping on an icon brings up a menu of options including Control Center), everything sort of falls into place.

Because it can display lots of windows placed utterly arbitrarily inside a 3D space, visionOS is, in some ways, the most Mac-like thing Apple has shipped since the Mac. Unfortunately, as we learned when Apple introduced Stage Manager to iPadOS, Apple’s modern operating systems have no foundation of window management. The lack of any organizational principles becomes readily apparent once you start scattering windows all over your house.

I know, I know, it’s a 1.0, and that means options come later. But window management should be high on Apple’s priority list. I’d like to be able to see a list of windows or running apps, retrieve individual windows from wherever I’ve left them, hide or show sets of apps, or even toggle between different “spaces” with different sets of windows—all of which are remembered. Everything feels so ephemeral right now. I have no confidence that anything I set up won’t be torn down the next time I put on the Vision Pro or move to a different room. And no window positioning seems to survive a reboot.

Apple made a great decision to allow iPad apps on visionOS, and the ones I’ve tried really work well. They also seem denser than visionOS windows, which I like—visionOS windows all seem a little too large, with big text and huge controls. Maybe that’s a function of an eye-driven interface needing big targets to hit, but the end result is that a workspace full of visionOS windows fills up fast, and ends up less dense than, say, a Mac with a big display or several displays. If part of the point of spatial computing is to take advantage of some of the productivity gains of having large or multiple monitors, visionOS apps seem to be scaled a bit too large.

This situation could be aided if Apple allowed them to be minimized in some way. Some apps, like Music, have the ability to be minimized into small windows that provide basic controls without taking up a lot of space. This is probably a concept that should be brought to every visionOS app. I find myself closing apps that are useful because I don’t need them at the moment, and they get in the way. I’d rather be able to minimize them into an icon or a small widget-like information display and then toggle them back to full size when I need them. I guess I’ll put that on the visionOS 2.0 wishlist.

To launch apps in visionOS, you can either use voice commands—”Siri open Messages” really does work—or tap on the Digital Crown to bring up the visionOS launcher. Just as in the early days of watchOS, Apple is content to provide a very simplified app launcher for its brand-new platform—it’s just an alphabetized set of icons, 13 per page. Obviously, that won’t scale. (I’m already fantasizing about being able to favorite apps or customize that first app screen.) Compatible apps from iPadOS appear in their own folder, called Compatible Apps, on the first page of the launcher.

Apps open in their own windows, right in front of you. Unlike on the Mac, all of visionOS’s controls are at the bottom of windows. The controls are a circle (which becomes a close box when you look at it) and a horizontal line (which lets you move the window when you pinch your fingers together as you’re looking at it). Pinching on a window and then relocating it is my favorite gesture in all of visionOS, a tactile experience that almost turns window management into a fun game.

To resize a window, you look at the bottom left or right corners, and the window controls slide over to become a curved indicator. When that curved indicator appears, you can pinch your fingers together and then move your hand to change the dimensions of the window. (iPad apps can have an additional icon at the top right of the screen, which you can use to change a window’s orientation from horizontal to vertical.) I found myself frequently frustrated when a window would refuse to get narrower or taller—presumably another legacy of iOS, where window resizing is pretty limited.

The primary input mechanism of visionOS is your gaze—literally whatever you’re looking at right now—and hand gestures. It takes some getting used to, but after just a few days, it felt natural to me. For this all to work, Apple’s eye tracking and hand tracking have to be close to perfect.

It’s very, very good, but I definitely noticed times when I couldn’t quite get the Vision Pro to recognize what I was looking at until I moved my head in that direction. Items at the periphery of the interface were the most likely to be difficult to select, and moving my head so that they were more central generally solved the problem. After a while, that movement also became second nature to me—a little like looking up a little bit when I’m reading so that the reading area of my progressive lenses is in the right place. Human brains are pretty adaptable, fortunately.

When it works, the detection of hand gestures also feels like magic. However, there is a learning curve. I kept realizing that when I looked to my left and tried to tap my fingers on my right hand together, it would sometimes fail—because the act of moving my head to the left had taken my right hand out of the Vision Pro’s field of vision. I imagine that I will continue to internalize these rules as I use the device, but it’s important to remember that it’s not magic or psychic and if it can’t see your hands, it can’t register your gestures. (Sure would be nice if my Apple Watch could use its sensors to register taps when my hands weren’t visible, though.)

I also found that, at times, I was plagued by non-gestures being recognized as gestures. Some of this probably goes down to Apple needing to improve its training models so that my fingers resting on the Bluetooth keyboard aren’t misinterpreted as being a tap, causing erroneous text selection. As my cat jumped onto my lap and I began scratching her head—only to wreak havoc on my Vision Pro interface—I also wondered if there should be a Siri command to temporarily lock out hand tracking.

While visionOS is Mac-like in terms of window management, it’s unfortunately iPad- and iPhone-like in its utter rejection of support for multiple users. Apple offers something called Guest Mode, but it’s severely lacking: It requires the primary user to be present, the guest has to undergo the entire eye-tracking setup process, and the moment the guest takes the Vision Pro off, all of that data is thrown away so the next time they want to use the device they have to start from scratch.

More than any other iOS-based product, Vision Pro is a product that deserves multiple-user support. In the past few days, I’ve found myself wanting to show various discoveries to my wife, only to realize she’d have to go through setup all over again… so I haven’t bothered. Even allowing guests to save their basic biometric data would be a step in the right direction, but true multi-user support really should exist. Optic ID, the biometric authentication system built into the Vision Pro, should be able to recognize different eyes and switch users, just as Touch ID does on macOS. The Vision Pro’s Light Shield, cushion, and corrective lenses are all made to be personalized and modular, so they can easily be swapped in and out. The same should be the case for users.

Speaking of Optic ID, it’s essentially transparent and magical when it works. You literally see an icon; the Vision Pro scans your eyes, recognizes them as yours, and unlocks the device. However, I struggled to get the feature to work consistently. It took me a half-dozen attempts before I could successfully enroll my eyes in Optic ID. Unlocking the device also frequently fails, leaving me to re-seat it on my head and open my eyes in a death glare until I finally get the thing to unlock.

It’s also a Mac accessory

One of the very best features of visionOS is Mac Virtual Display (MVD), which lets a nearby Mac put its entire interface in a Vision Pro window. This is a feature that probably won’t replace a nice, big monitor for most people—you can get one of those for a lot less than the cost of a Vision Pro—but is an amazing way to make a 13- or 14-inch Apple laptop suddenly act like it’s got an expansive desktop display, no matter where you are. This will be especially great in tight spaces like airplanes and hotel rooms.

In general, I found text on an MVD to be less sharp than text from iPad or visionOS apps, though if you blow the screen up big and lean in close, it still looks pretty good. Having access to a Mac window inside of visionOS also immediately makes the entire system more functional since the Mac can still run all sorts of software that Apple’s other platforms just can’t run.

And it gets better. Because when you use a Mac (any Mac, not just laptops) with Vision Pro in MVD mode, your Mac’s keyboard and trackpad automatically connect to your Vision Pro via Universal Control, a feature that rolled out a couple of years ago that let you do things like drive an iPad from a Mac, or a Mac from an iPad using a Smart Keyboard. Universal Control was a fun feature as it was, but I’ve now placed a new strand of red yarn on my conspiracy board as I begin to suspect that visionOS was the endgame for Universal Control all along.

In any event, you can use your Mac’s trackpad to control every item in your virtual space, not just the Mac itself. Want to scroll over to an iPad app off to the left? Just move the pointer off the Mac in that direction, and it pops into the iPad app with the telltale iPadOS circular pointer. You can even click and drag to rearrange visionOS windows in virtual space. It feels revelatory, like seeing the matrix.

Bless the hearts of OS daredevils who will build up visionOS productivity systems using nothing more than a paired keyboard and trackpad, but for my money, the ultimate visionOS productivity setup will pair a Vision Pro with a MacBook on your lap. It’s like using a Mac that can also project holograms.

The silver screen

So much of the story of this product is about what it’s trying to become and where it’s going—and rightly so. But if there’s one place where it feels like the Vision Pro has already arrived, it’s video playback.

I’ve spent quite a bit of time watching 3D movies on the Meta Quest 2 and 3, enough to make me realize that solo entertainment is absolutely a use case for these sorts of devices. And the Vision Pro leaves me with no doubt that this device’s display—two separate tiny OLED displays, each of 4K-ish resolution, one for each eye—is the absolute best on the planet in a consumer device.

The Vision Pro creates a legitimately great movie-watching experience. 3D movies look much better than they ever did in the movie theater since they’re being beamed at full brightness right into your eyes. Since we’re all so familiar with “flat” 2D content, it’s actually a great way to judge the displays since there’s no real novelty in watching a plain old YouTube video or a TV show. The image quality is superb.

It’s the immersive stuff where Apple has really transcended my expectations. These are stereoscopic views with near-180-degree fields of view, and they feel unlike any sort of entertainment form I’ve experienced before. But they also feel new and experimental, which is exciting. Is it better to shoot these videos like traditional films, with different perspectives and cuts, or to keep the camera still, like we’re a fly on the wall of a special scene? And should the subjects of these videos engage with the audience, or will we be creeped out and want to hide when Alicia Keys sings directly to us?

The only solution is for Apple and its partners to just try everything. Recordings of live theater would be amazing in this format. So would concerts. (Taylor, record an immersive version of Eras Tour for Disney+!) And most of all, sports will shine in this format. Apple has existing relationships with sports leagues as well as sports rights holders. I hope that in the next few months, we see immersive highlights and maybe, just maybe, an attempt at live immersive broadcasting. Take me courtside. Put me in the dugout. Let me float above a soccer pitch.

Another way of immersing yourself in media is by opening multiple windows of content at once. Unfortunately, the relatively rudimentary multitasking functionality of iOS and iPadOS is going to bite visionOS. This device should be ideal for watching multiple streams of content: Imagine playing the NBA on Max to my upper left, ESPN on my upper right, and the MLB app dead center!

You’ll need to imagine it, because it doesn’t work like that. Instead, what generally happens is that when you play one video, the other video stops. I don’t like this on iPadOS, but it’s deadly on visionOS. It needs to be like the Mac, where I can open multiple apps and browser windows and have a bunch of different audio and video playing, and it’s no problem. If I create a cacophony, that’s my problem—I created it, and I can sort it out myself! visionOS needs to be similarly unchained in this regard.

On top of that, app developers need to let their apps spawn as many different windows as their users want. I should be able to put myself at the center of an Adrian Veidt-like video wall in my Vision Pro space if I want.

Are you not entertained?

Unlike every other VR headset in existence, the Vision Pro’s marketing hasn’t been focused on games. Still, at launch, Apple made sure there were several Vision Pro games available in Apple Arcade. These aren’t the kind of immersive experiences we’ve come to expect from VR platforms, though. Instead, there are some augmented-reality experiences (What the Golf and Game Room both put their game boards right on my living room coffee table), and even the more familiar VR games (Synth Riders, Super Fruit Ninja) took place in my actual space, with the occasional portal into another world.

It’s not just Apple’s philosophy that the Vision Pro is primarily for augmented experiences rather than replacing all of reality with something new—it’s also that the input mechanism on the Vision Pro is based on hand tracking. There are many advantages to using hand tracking, most notably that you aren’t required to grab a couple of controllers every time you put the headset on. But controllers are really, really good for video games because they offer precise input (both in terms of motion and in terms of button presses) that hand tracking just can’t.

Unless Apple or a partner decides to build optional hand controllers, Vision Pro games are probably going to be more slanted toward simple interactions, 3-D object experiences, and games played with traditional game controllers.

I’m not convinced that games like Synth Riders and Super Fruit Ninja are going to work. I’m not exactly an expert Beat Saber player, but I do enjoy it; playing Synth Riders felt imprecise and frustrating. Super Fruit Ninja feels like a game that could legitimately have been designed for the Meta Quest, but the game kept missing my hand swipes. It just didn’t feel like this was the sort of input the Vision Pro was designed for.

Capturing 3-D memories

The Vision Pro isn’t just a 3-D display; it’s a 3-D capture device. Cameras on both sides of the Vision Pro allow you to capture spatial video and still photos, and you can also view spatial videos shot by the iPhone 15 Pro.

It’s a give-and-take. Videos shot in 4K HDR are going to look way better than videos shot today in spatial formats, but they’ll lack that magical depth effect. Videos and photos that are close to subjects and where there’s action happening in multiple levels of depth are going to pop in 3-D; landscapes and other “flat” subjects would benefit from being shot with the highest quality camera setting you can choose.

But Apple is on to something with its 3-D captures: Looking at intimate stereo captures has a way of creating an emotional, visceral response that flat images don’t really replicate. (There’s a reason Apple’s demo videos frequently involve kids.) I don’t know if this sense will fade as we all get used to watching 3-D captures, but it’s accurate to say that watching a 3-D image of your own life feels a bit like stepping back into a frozen memory.

The spatial videos captured by the Vision Pro look better than the ones captured by the iPhone 15 Pro, at least to my eyes. They’re square rather than wide, and the increased distance between the two cameras means the 3-D effects are more pronounced. That said, I’m not going to be toting my Vision Pro out in public to capture key life events, so I’m glad that the iPhone 15 can shoot spatial video and I will try to remember to take more of it in the future! I just hope that on future models shooting spatial video isn’t such a compromise to picture quality.

Now, let’s talk about the real, unexpected star of the Vision Pro media experience: panoramas! I’ve been shooting panoramas for years, even back to the days of film cameras. (I was building Quicktime VR panoramas in the 1990s!) The iPhone has been able to shoot panoramas for a very long time now, and you can view them on your devices, and they look… fine. They’re wide. Great.

But view them on a Vision Pro, and they’re gripping. visionOS takes your panoramas and expands them to fill as much of your view as they possibly can, removing distortion and mapping them on the 3-D space around you. They’re not full 360 images, of course, but they’re still really impressive. I kind of want to use some of them as environments! (Note to Apple: using generative AI to transform panoramas into 360 environments to be used in Vision Pro would be swell.) I didn’t have quite the emotional response to panoramas of long-ago vacation scenes as I did to 3-D videos and pictures, but it was close! Seeing a friend give a toast at another friend’s wedding, and being able to look around to spot other people in the crowd… that was special.

Digital Doppelgänger

How do you let people wearing VR goggles on their faces participate in videoconferences? It’s a real problem, and Apple’s solution is more ambitious than the one most of us had been expecting for years. With Memojis, Apple built an entire cartoon avatar system that could be (optionally) personalized and would dynamically react to your facial expressions. Then it chucked the whole thing in the bin and built Digital Personas instead. (Part of the decision might involve that Memojis are built using Apple’s older SceneKit technology rather than the new RealityKit that’s the foundation of visionOS.)

Digital Personas are technically amazing. To create one, you take off the Vision Pro and hold its sensor-laden front toward you. It scans your face, asking you to turn left and right and up and down, smile with and without teeth, raise your eyebrows, and close your eyes. From this, it builds (in a very short period of time, maybe 30 seconds?) a 3-D replica of your head that’s animated in real time based on your facial expressions, which are detected using cameras inside and outside of the Vision Pro. It is absolutely amazing, bananas technology on both sides of that equation, and the result is that if you’ve ever wanted to be a character in a video game, now you can be!

As impressive as the tech is, it’s not quite all there yet. The “uncanny valley” is a famous concept about making something just real enough that our brains rebel at its unreality, and it’s a fair criticism of Digital Personas to say that they tend to fall within it. They are simultaneously incredibly impressive and not quite good enough, at least out of context. I struggled to get my Digital Persona to look anything like me, and it still looks like my face has been stuck on the front of a brick.

But a funny thing happened on the way to me slagging Digital Personas: I spent time in FaceTime calls and Zoom calls with friends of mine, all of us using our Digital Personas. And in that context, where it’s your friend’s voice and conversation and facial expression cues, it gets a lot easier to forgive or accept the weirdness of the Digital Personas. As stills, out of context, Digital Personas are off-putting. In the context of a conversation, they’re okay—and I assume they’re only going to get better from here.

Apple’s got a lot of work to do on Digital Personas beyond just making them better. First off, visionOS should be able to store more than one at a time and should offer more customization options (like quickly swapping eyewear preferences). When you make a Digital Persona, that look sticks with you—put on makeup or a suit, and your Digital Persona will always look like that. That can be cool—you don’t have to primp for your next meeting!—but it also forces your persona into the same context at all times.

And then there’s the issue of people not particularly liking what their persona looks like or how it represents them. Apple needs to offer alternatives to Digital Personas, ones that are less realistic or more generic so that people who are uncomfortable with their personas aren’t locked out of using video conferencing when they’re using a Vision Pro. As one friend of mine said to me, “I don’t want to use my dumb old face—I want to be a cool space monster!” You could do that with Memoji, and it should be a direction for Digital Personas, too.

The eyes of your Digital Persona can also populate the EyeSight display, a separate outward-facing display that acts as an indicator of what you’re doing (including if you’re capturing video or photos). If you can see a person in the real world and they can see you, Vision Pro puts a version of your Digital Persona’s eyes on the screen to make it look like you’re seeing through the Vision Pro hardware. Sort of. I don’t really have a lot to say about this feature other than that externally indicating status is important and that it probably didn’t require the added cost and weight of a whole display.

So is this the future?

When I was a kid, they told us we needed to learn about computers because they were the future, and that assumption was proven right. But does the Vision Pro represent the future of computing?

Apple certainly believes so. The entire design of the Vision Pro and visionOS is focused on augmented reality first, and for a reason: This is Apple’s attempt to slowly build toward a product that is as unobstrusive as glasses but offers all the same augmentation powers as the Vision Pro. That kind of display hardware and miniaturization doesn’t exist now—it’s probably a decade away, if not more. But the fastest way to get us there is for Apple to ship the Vision Pro and drive both hardware and software development forward toward that goal.

The reason Apple is doing this is because more than half of its business is the iPhone, and that means one of the few existential threats to Apple’s success as a company is some future tech that makes the smartphone obsolete. A device that’s as powerful as a smartphone but is projected entirely into our own vision is a pretty good candidate for that.

In the long run, I think that augmented vision is inevitable, and by spending decades on this technology, Apple is going to position itself to be a major player in that field. Software developers and hardware manufacturers should be paying attention.

But regardless of whether or not something based on visionOS is the computing product of the future and a huge source for growth for Apple in the 2030s, the Vision Pro is a real-life product today. And it needs to be judged as such.

Leaving price aside for the moment, I think it’s worth considering what the Vision Pro is good at. It’s a great movie player, offering 3-D and immersive experiences that go beyond anything else that’s out there. It’s also an iPad-level computing device that can optionally integrate with the Mac to take a small laptop screen and make it part of a larger world. I’m not sure whether a lot of people will want to spend their entire workday inside a VR headset, but the last few days have taught me that I can certainly do it, and it’s just fine.

Compared to those early personal computers, the Vision Pro is actually a better value, thanks to the existing software ecosystem that allows it to be useful right out of the box. But still, this is a product you buy either because you have a very specific use case that makes it worth the cost or because you just want to have a taste of the future. (No judgment here.)

At least there are clear use cases. Even with immersive video in its infancy, it’s a great solo entertainment device, so if you find yourself watching movies and TV without other people around, it might be worth it. If you travel a lot and find yourself in cramped airline seats and tiny hotel rooms, or if your home or office is too small to fit a full desk setup with a big monitor, you’ll find that the Vision Pro is a bit of a TARDIS3: everything’s bigger on the inside.

It’s fine if none of those use cases fit you—this is a pricey first-generation product that’s finding its way. But it might still be worth musing a little bit about where the product might go. It’s easy to imagine visionOS evolving—1.0 operating systems have nothing but green fields of space to grow and develop—and early adopters and app developers will help steer the platform’s direction. Most notable to me is the device’s lack of proper sharing features—there’s no way to get the feeling that another Vision Pro user is present in your space, and even if there are two people in the same physical room, both using Vision Pro, they can’t look at the same virtual objects.

On the hardware side, there’s also plenty of room to grow. This may be the cutting edge, but that display could get even better, with support for higher resolutions and frame rates. The field of view also needs to get wider—it’s currently about what I can see in my glasses, but the blackness in my peripheral vision means that I rarely forget that I’m wearing a headset. The device needs to get light enough to integrate a battery and then get lighter still. The sensors can improve so that the passthrough video looks even more realistic. And, of course, improved CPU and graphics power will bring more realistic rendering of virtual objects, including those Digital Personas.

Perhaps most importantly, the very name Vision Pro implies that there will one day be an Apple Vision, a product that’s more affordable and presumably will ship in greater quantities.

Coming of age at the moment that computers began appearing in homes and classrooms had a huge impact on my life. We were exploring technology so new that nobody really understood what it was for or what could be done with it. You can draw a direct line from the first time I typed in a BASIC program to my choice of career.

I don’t know if the Vision Pro will predict the future like those early computers did. But I do know that it’s so new and weird and interesting that it brings back all those feelings of wonder and enthusiasm and curiosity that I felt in those early days. Wherever this product goes, whatever it does, it’s certainly going to be a fun ride.

- Panic’s Playdate, an indie handheld game console with a little flip-out crank, is a similar example. More radial input devices, please! ↩

- Apple should just make a keyboard/trackpad combo deck for this thing. In the meantime, TwelveSouth will sell you a MagicBridge for $50. ↩

- The time machine in “Doctor Who,” which is tiny on the outside but enormous on the inside. In other words, the Vision Pro lets you make tiny spaces seem enormous. ↩

If you appreciate articles like this one, support us by becoming a Six Colors subscriber. Subscribers get access to an exclusive podcast, members-only stories, and a special community.