By Jason Snell

December 14, 2020 9:00 AM PT

20 Macs for 2020: #3 – Macintosh 128K

Note: This story has not been updated since 2020.

My friend John Siracusa is disappointed in me because I didn’t put the Macintosh 128K—the original Macintosh—at number one in this list of the 20 most notable Macs of all time.

I certainly considered it. The original Macintosh changed the computer world forever. Without its presence, this series couldn’t exist. It is a seminal product in the history of technology.

Putting it at number one felt a bit obvious, though. And there’s this: While it came first, it had a lot of drawbacks—so many, in fact, that it was revised within a year. It was a remarkable first attempt, but for my money the Mac didn’t really settle down as a platform until the Mac SE arrived in 1987.

But still, it was first. And that counts for a lot.

First of its kind… sort of

You think you know the story. (And if you don’t, please read Stephen Levy’s Insanely Great and Andy Hertzfeld’s Revolution in the Valley.) A team of pirates and rebels at Apple came up with something new, something never seen before in the personal-computer world, and it changed everything—eventually.

But first, on a day in January in the early 1980s, Apple introduced a revolutionary new computer, driven by an unusual input device called a mouse, and featuring a novel graphical interface. Except this isn’t the year you’re thinking of. It’s January 1983, and the computer is called the Lisa.

We never talk about the Lisa, because the Mac went on to spawn an industry that continues to this day. But the Lisa was built by a lot of the same people, and in many ways was more advanced. It came with a hard drive, while the Mac relied only on floppy disks. It had more memory, as well as an advanced operating system featuring protected memory.

Unfortunately, the Lisa also cost nearly $10,000—the equivalent of about $26,000 in today’s dollars—and was targeted at a business market that wasn’t interested. Meanwhile, Steve Jobs got kicked off the Lisa team, took over the Mac, and aimed that computer more at the masses. Compared to Lisa, the $2,495 Mac was almost a bargain, but in broader terms it was still pricey1 when introduced a year later.

The Lisa wasn’t a Mac. But it’s not fair to give the Mac all the credit for the change that it wrought in the computer industry, either.

Enter the mouse

In the early 80s, everyone knew what a personal computer was: It was a box that displayed blocky, monospaced text on a screen. You’d type commands. Sophisticated programs might have their own help system to tell you which keys to press or how to move a blinking cursor around on the screen, but interfaces were completely different from program to program. There were graphics, too—blocky ones, used mostly in game programs.

The Mac broke all those rules. Every single one of them. Everything on the Mac was a graphic. Your primary method of interaction was by pushing a pointer around on the screen by way of a new peripheral, the mouse. You ran programs by clicking on the icon that represented them. Their commands were all visible via the menu bar at the top of the screen, organized by category. You could learn what a program did by just clicking through the menus.

Similarly, the file system was browsable (via the Finder app) as a series of icons, or windows with lists of files. You could drag a file from one place to another, or ready it for deletion by depositing it in the Trash. In a move that prefigured emojis by a few decades, friendly iconography was everywhere—including a smiling Mac that welcomed you when you turned the computer on.

The nine-inch screen—even tiny by the standards of 1984—was a marvel. It was black-and-white, but what it lost in color it gained in resolution. Every one of those 175,104 pixels was crystal clear. Unlike other computers, it displayed black text and graphics on a white background, like ink on paper. And the text could even be in different typefaces, a far cry from the individual monospaced command-line font on most computers of the era.

Early-80s computers that offered color were saddled by hazy, low-resolution monitors—or even worse, the family TV set. The Mac’s display was colorless, but it was sharp. The first time I saw a Mac, I couldn’t believe what was on the screen. The graphics were colorless compared to the Apple II, but they were shockingly fast-moving and crisp.

Of course, that display was a part of the Mac, not an add-on. In that era, that was fairly uncommon, too—though the first computer I ever used, the Commodore PET, also had an integrated display, and early models even had an integrated tape drive for storage! But many other computers, including the Apple II, were much more modular.

The goal with the Mac was simplicity. Personal computers of the era still bore the marks of emerging from a messy hobbyist culture, invented by people who didn’t think twice about soldering, pulling chips, flipping DIP switches, and the like. To reach a broader audience, though, Apple needed to simplify everything.

And on that score, I think the original Mac was pretty much perfect. The point-and-click interface was explorable even if you knew nothing about how the computer worked. That put it miles ahead of all the computers that would just sit there, cursors blinking, awaiting input of a very specific kind and beeping at you if you typed in something wrong. The Mac was self-contained, with a little carrying handle, so you could plop it down anywhere and start using it—no heavy wiring required.

Even the use of the 3.5-inch diskette was an inspired choice. Most computers in that era still used 5.25-inch disks. These truly floppy objects included media areas so exposed that it was perilously easy to put a finger on one or lay the disk down carelessly without inserting it in a protective sleeve, ruining it. The Mac’s diskettes were rigid, with a spring-loaded door that was closed when not in use, making them far safer.

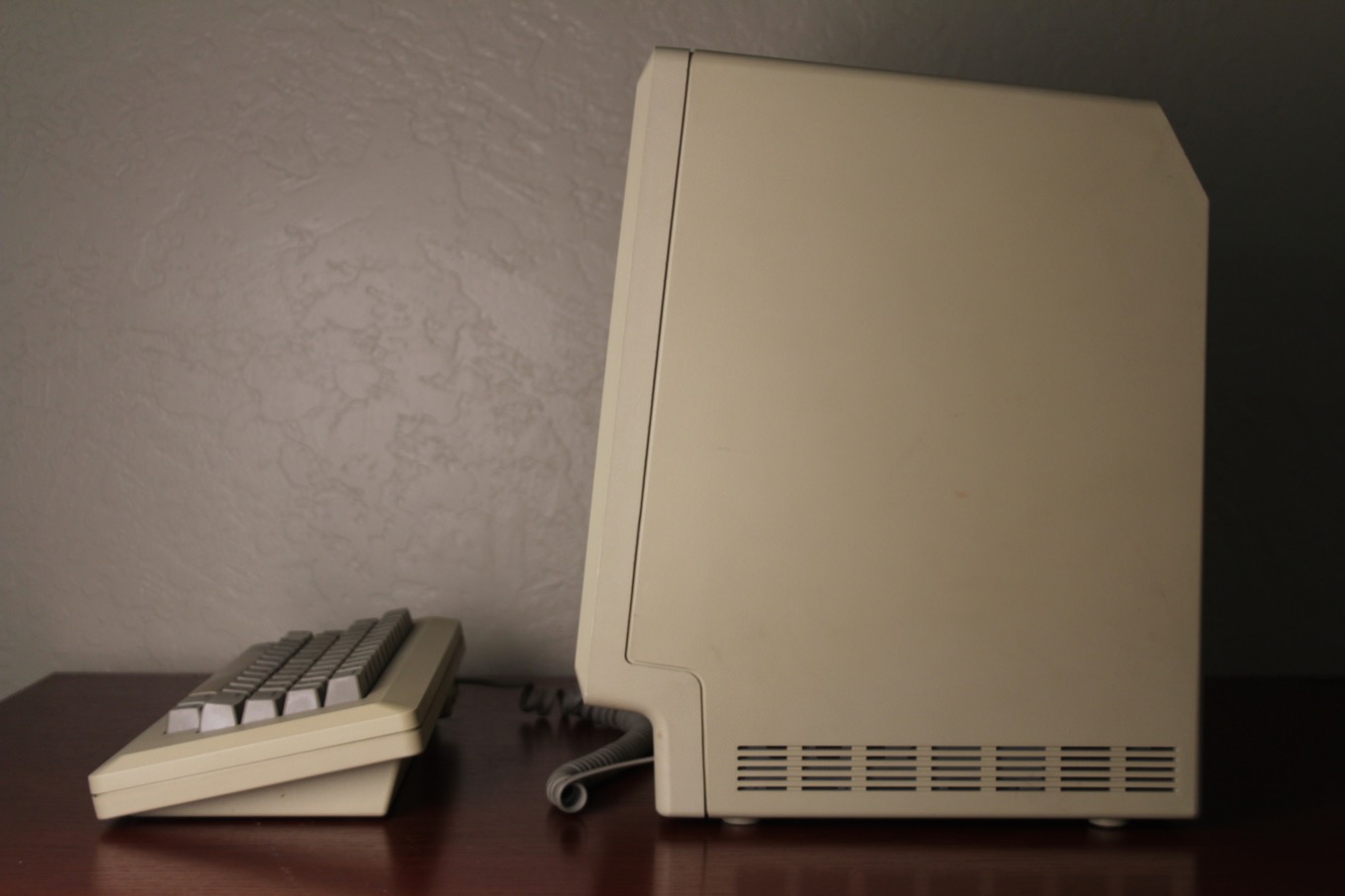

And the shape of that squat, friendly original Mac just can’t be beat. It’s perfectly represented by Susan Kare in her famous icon set, beaming with a smile—or dead with its tongue stuck out because it has crashed and burned. It was a computer with a warm, fuzzy personality—and at the time, that was revolutionary.

A work in progress

As amazing as the original Mac was, it was kind of a weird Mac. There were three DE-9 serial ports on the back, one dedicated to the mouse, the others to allow connection to an optional printer or modem. These were truly old-style ports, the kinds with bolts on either side so you could screw the cables in so that they were semi-permanently attached. Only these earliest Macs have these ports. They’d be replaced in the Mac Plus and thereafter with rounded serial ports that would last until the introduction of the G3 iMac, and beginning with the Mac SE the Apple Desktop Bus for mouse and keyboard input.

The keyboard was odd, too. Apple chose to release a keyboard without arrow keys—a decision that forced developers of Mac software to support mouse control rather than just emulating the keyboard-driven interface of other PCs. It connected to the Mac via a coiled telephone-style cable with RJ-10 modular jack.

While using a 3.5-inch diskette for storage was inspired (and almost didn’t happen), the minuscule 128KB of RAM on the original Mac combined with the 400K limitation of the disks meant that users frequently ended up in situations where access to a second disk was necessary.

Apple had cleverly designed a system that let the Mac use more than one disk. You’d eject the first disk, but it would stay visible on the Desktop, grayed out. Then you could insert another disk, and use it to save a file or launch a program. The problem with this approach was that the system would sometimes need to check back to that first disk. And with its small amount of memory, that happened a bit more often than you might like.

This all led to one of the core experiences of the earliest Macs: Your disk was spat out, and you’d be told to insert the other disk. This would often happen multiple times, as you swapped back and forth. (If you had the money, you could connect an external drive via the large DB-9 floppy disk port, in order to keep from endlessly swapping from one disk to another.)

Apple realized pretty fast that the low memory of the original Mac was going to be an issue. Nine months after the first Mac was introduced, Apple rolled out a second model—the Macintosh 512k—that increased onboard memory fourfold.

In these early days, Apple was finding its way. You have to walk before you can run. With the introduction of the Mac II and the Mac SE in 1987, the Mac became a platform. These early compact Macs, from the original through the Mac Plus, were exciting and revolutionary—but compared to all the Macs released up through 1998, they were outliers.

It’s why we’re here

There’s one more notable thing the original Mac helped create that needs to be mentioned—something that’s still going strong 36 years later. That’s the community of people that grew up around the Mac, who embraced a quirky and cute little computer and shared their enthusiasm with others.

Choosing to use a Mac has always been a decision that goes slightly against the flow. The Mac has never, ever been the choice of the masses. There’s something special about being a Mac user.

While the Macintosh 128K was underpowered compared to the Macs that were built just a few years later, it was the first Mac. And while it wasn’t even the first Apple computer to feature a mouse and a graphical interface, it was the one that caught on and transformed the future of computer interfaces.

John Siracusa is right—the original Mac is the one that started it all, and that’s worth an awful lot when it comes to considering the most notable Macs of all time. As he told me:

If the parameters of the discussion come anywhere near importance, or the most revolutionary, or the most personally impactful, or any of those things that say, ‘What kind of ripples in the pond did this computer make? What put a dent in the universe?’ If that’s any part of your criteria, it’s very difficult to make any argument against the original Macintosh. Everything that came after it started with that one.

Indeed it did.

I’ll see you next week with number two.

- You could get an Apple IIe with a disk drive and display for less than $2,000 in 1984. ↩

If you appreciate articles like this one, support us by becoming a Six Colors subscriber. Subscribers get access to an exclusive podcast, members-only stories, and a special community.